On Guilt, Repentance, and Atonement

The dreadful yet necessary and enlightening condition of human existence

We all have skeletons in our closets. Words and actions, said and done, we deeply regret. They stain our memories to remind us of something we detest grappling with. Resting our attention on them crushes our hearts and souls more than anything else. And yet a glimmer of light shines through the dark if we keep the window open. It's your story as well as mine and Raskol'nikov's, the (un)fortunate protagonist of one of the greatest tales ever written.

It all starts down there, deep within the void. At first, we don't know what it is and yet feel it. Limbs sprout from it and the formless, bloodstained mass gains a familiar semblance. The guilt, that is, an insufferable companion. He grows stronger and more sinister. He then seizes us by the neck and hurls us to the ground: it's time to wrestle. The fight rages on; we are drenched in sweat while the demon remains unscathed, poised to deliver the final blow. But the demon's not an enemy. Quite the contrary, he's there to help. What we feel as low-kicks are wake-up calls. Our indifference frustrates him as acknowledgement's all he desires. Escaping from, or even worse ignoring him, can only prolong the agony, because who we are escaping from, truly, is ourselves.

Here we reach the second stage: repentance. Whereas guilt’s protean form seeps into the crannies of our minds and its manifestation remains elusive, repentance requires delicate yet decisive, rational maneuvers. Awakening to the guilt opens a door wherein we stretch or compress or scream or self-mutilate while the demon watches all the while. What will we do? Are we going to swim in a sea of self-exonerating justifications, fall into a canyon of self-deprecation without chance of rising back up, or perhaps be honest with ourselves and find the courage to change?

It's Raskol'nikov's tale, master of all sins, who spends what he perceives as eons trapped in vivid, all-too-vivid, nightmares. The demon knocks, takes over, and makes him even more miserable than he was before the crime — that very same crime intended to elevate him. Raskol'nikov struggles with his guilt and he isn't even aware of it. He can't understand what's wrong. He kills the greedy, despicable granny to free himself from her tentacles. He's supposed to use her money to finish university and live up to his poor mother and sister's expectations. Yet he doesn't last a second. He hides the money to never retrieve them and spends the aftermath of his crime in an unrecognizable state, instead. He's not the Raskol'nikov he and everyone else knew; he's changed to never go back. His rationale says things promptly contradicted by the guilt taking over, until no solution presents itself at the horizon other than atoning, submitting himself to the law. Raskol'nikov could no longer move; he could only speak, breathlessly imploring forgiveness. It is in fact in prison that he realizes how self-delusional he'd been. Throughout the crime's investigation, he subtly and subconsciously desires punishment, highlighted by the numerous attempts to sabotage himself.

Raskol'nikov is testament to two things. First, that in order to repent we must first clearly understand the source of our own guilt, and that the path isn't straight by any stretch of the imagination. It's like that old game, Snake, folks born before the 2000s like me used to play on their Nokias. We move left and right, up and down, devouring experiences until our own flesh is all that's remained to consume. As the demon is fed and grows, the room feels suffocatingly smaller and smaller, and the chances of a close combat become as high as its necessity. It's time to settle the dispute.

Second, corrective action must follow the stage of rationalized repentance for someone to atone. No excuse, no steelmanning of the sources of our guilt stands a chance, on the one hand. No bringing ice into the artic by self-beating into stillness can redeem us either, on the other. We ought to be honest with ourselves, yet we can let no degree thereof pull us into its immobilizing gravitational center. Words and thoughts without actions are worthless, and equally so are their inauthentic versions. A truly repented person seeks atonement independently from its consequences, be these years in prison, as for Raskol'nikov, or their peers' hatred. Corrective action must be genuine, in the sense that it should be ascribed primarily to the actor's internal will to change rather than external circumstances such as law enforcement, otherwise it's spurious and inconsequential. We must be "breaking the habit", to quote Chester Bennington.

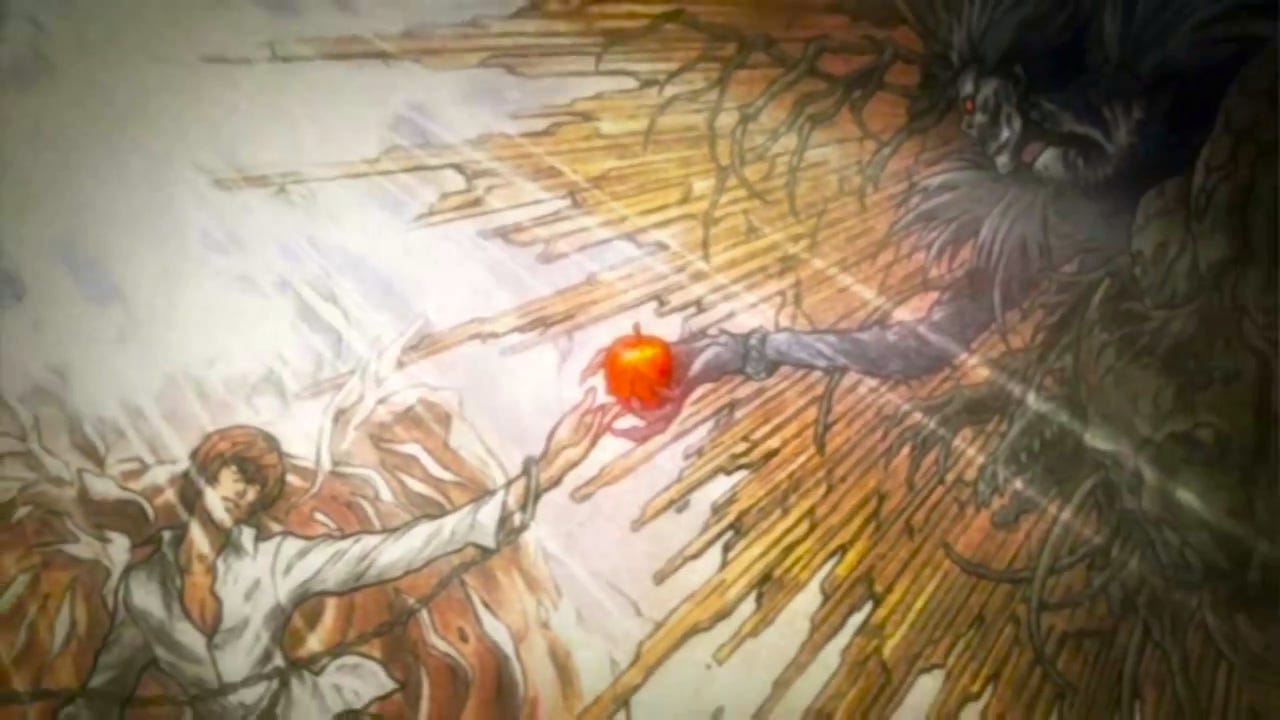

Here I arrive at another fictional example, a truly heartbreaking one, too. It's from a spin-off iteration of Death Note, my all-time favourite anime and manga. At any rate, we know the protagonist partook in a terrible crime, the victim whereof is a young woman. He didn't architect the idea himself but ended up going along with it anyways. Years pass, he's built a new life, he's a good person now, yet his actions never cease to torment him. He's like a moth circling around a candle. He even refuses to marry his beloved partner, admitting to her he's not worth it. No degree of consolation on his partner's side can override the guilt. The death note's holder finds him shortly after, writes his name down, yet nothing happens. His repentance was genuine to the degree that he became another person entirely. He'd changed such that the lethal death note couldn't bring about his death: his name had changed. However the power of the Shinigami's eyes had the best of him at the end.

From unnoticed guilt at the outset to genuinely rationalized repentance at the second stage: that's quite a bit of progress made. When can we consider ourselves atoned? Atonement is, to my estimation, to be viewed through both a personal and societal lens. On a personal level, rationalizing the guilt and activating ourselves to ensure nothing like what we did repeats constitutes the only possible solution. Insofar as it's done to change and not primarily for fear of external consequences, I consider someone atoned. Both Raskol'nikov and the protagonist of the Death Note's spin-off were, as such, atoned. But that's only one side of the coin. Victims of rape will most likely never forgive the culprit. Little do they know the perpetrator may be fighting their demons, and even if they did, they're not obliged to express their pardon. We must in fact face the consequences of our moral and legal system, be our peers' hatred, exclusion from social practices, imprisonment, fines, and so forth. The truly repented individual knows and accepts this. Of course, the assumption of proportionate punishment to the crime must stand. There can be cases where someone's unjustly kept on the hook for something they've done.

I’ve been watching Lucifer lately, where we follow the all-too-human Devil’s adventures in our world. We get to know how Hell works, and to me, it’s a perfect depiction of the process I’ve described. Those who end up in Hell live in their own private torture chambers, where they are forced to relive their worst regret — on repeat, forever. What is your worst regret? When did you reach your lowest point? Which episode evokes the most guilt? That’s your Hell. And you remain trapped until you realize you deserve it. But even that is not enough. The sinner must also forgive themselves to be set free.

This is exactly what I have been trying to describe. First, guilt must exist. Second, we must acknowledge and understand it. And third, we must atone by actively changing the very foundation of that guilt. Lucifer’s Hell shows that not everyone carries guilt to begin with—some refuse accountability, while others are consumed by it, unable to forgive themselves. The only escape is to embrace the demon, make room for him, and ride alongside our newly found companion — towards the next blunder.

This is great and amazingly written. Well done - thank you for these reflections